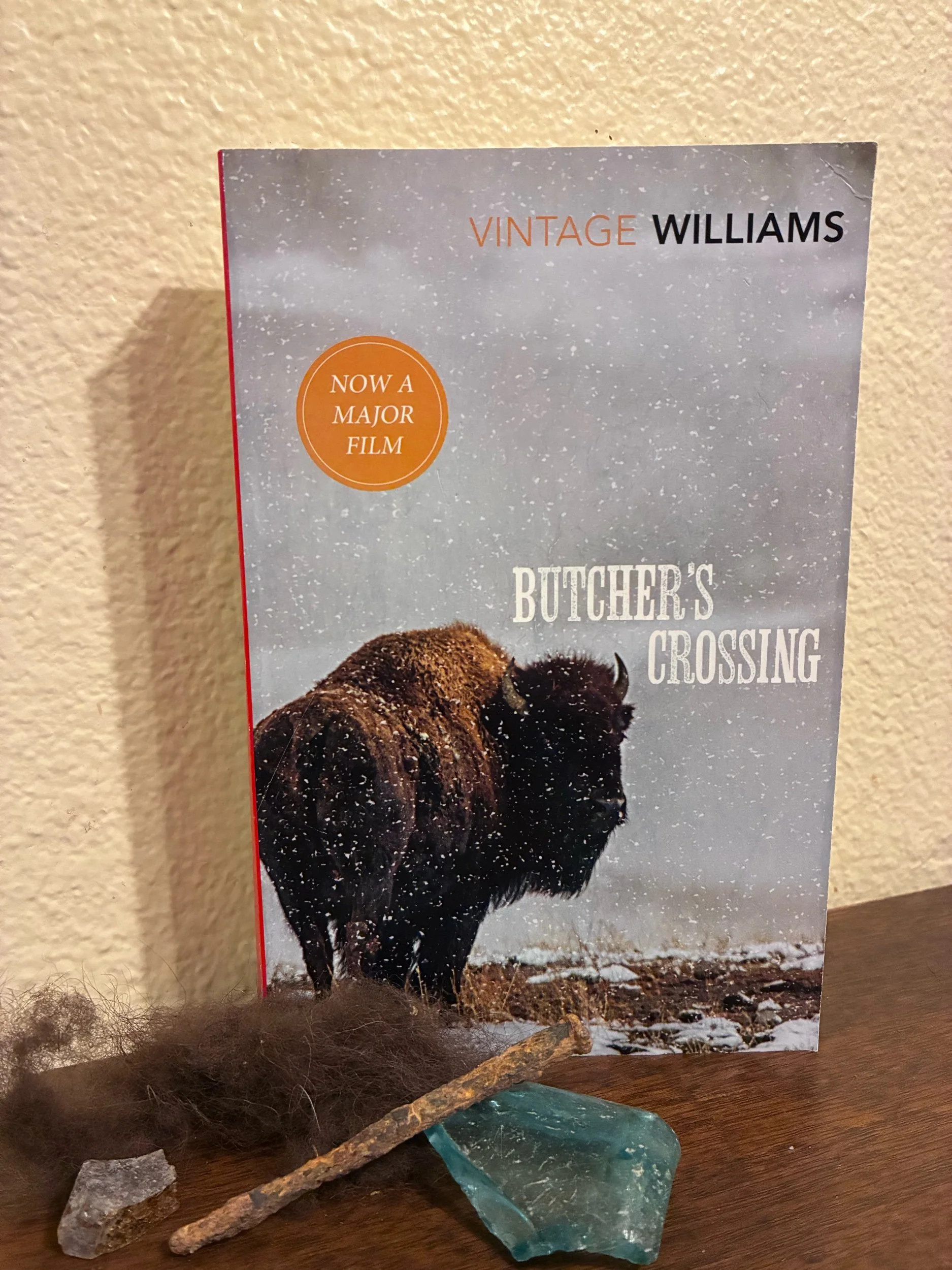

This fall I lost myself in the wilds of John Williams’ Butcher’s Crossing (1960) and quickly recognized its power and its brilliance. This western novel follows the path of Harvard student, William Andrews. Andrews leaves the comforts of civilized life back East to venture westward. It is the age of the great bison hunts, of making one’s fortunes in the unclaimed lands of the American West; it is the late 1800s and the romance of the West calls young Will Andrews.

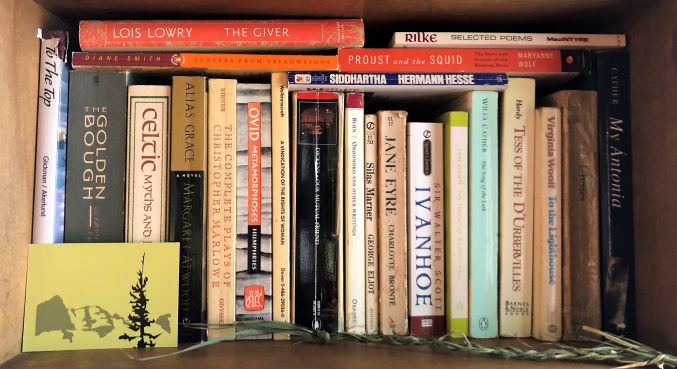

A few of my favorite reads…

CONTEMPORARY & CANONICAL ǁ NEW & OLD.

Fiction ※ Poetry ※ Nonfiction ※ Drama

Hi.

Welcome to LitReaderNotes, a book review blog. Find book suggestions, search for insights on a specific book, join a community of readers.