The Serviceberry

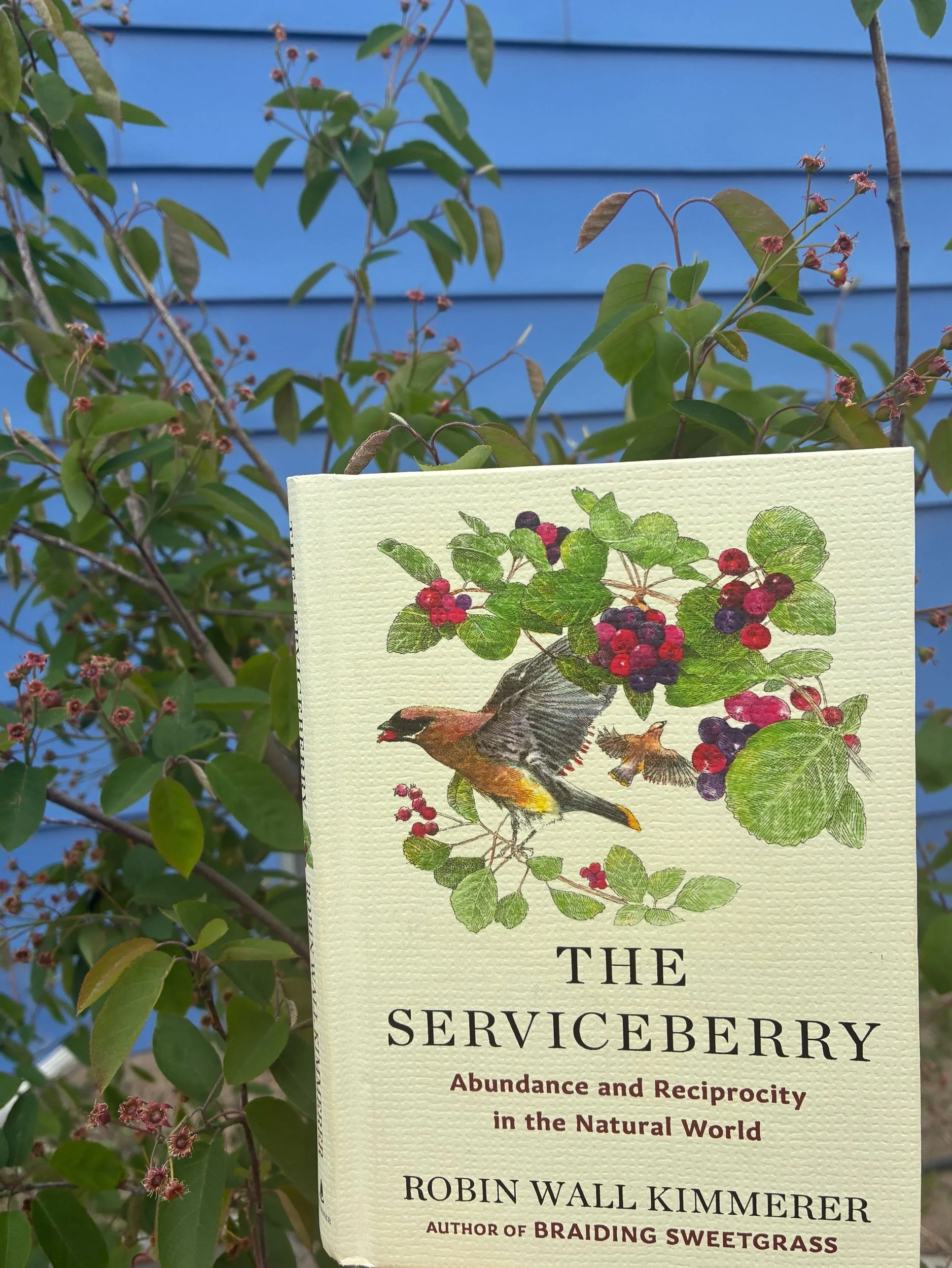

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s most recent book, The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World (2024) is delightful in both size and subject. Beautifully illustrated by John Burgoyne, this small book fits perfectly in one’s hand. It is a gift to be treasured. And what could be more perfect? Such a lovely, petite hardcover, adorned with illustrations, and readable in a good sitting, The Serviceberry is a book all about gift economy. Its just-over one hundred pages offer up an ethnobiologist’s perspective on ideal economic relations through a meditation, in part, about the serviceberry and the contrasts between the extractive, scarcity mindset of modern capitalist systems and gift economies of indigenous societies.

This book reads like a rambling conversation with a brilliant mind. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s begins by describing the collective delight in harvesting juicy serviceberries—an unexpected gift—with a crowd of winged friends. From that gift she unspools the concept of a gift economy and contrasts it to the commodity economy. In the former, all members care for gifts and do not take more than is necessary; in the latter, exploitation and storing excess for our future selves is the norm. Gift economies are communal; commodity economies are individual and extractive. Kimmerer explores the components of both systems. She provides examples of the gift economy in both ecology and modern civilization. Ultimately she poses the question: what if scarcity is not as fundamental an issue as our economic system suggests? What if there is plenty of everyone if we care for what we have and share with one another? Indeed, these are the underlying tenets of a gift economy.

The Serviceberry is essentially a meditation on possibilities of biomimicry. Kimmerer invites readers to join her in the thought experiment made real by embracing gift economies in small, close-knit communities through things like little free libraries and free farm stands. When we embrace gratitude for the gifts we receive and meaningfully connect with others, Kimmerer is undoubtedly right, our lives will be richer and more satisfying. The gift economy of the serviceberry (of which we humans are sometimes a part) is one worth aspiring to; just as reading Kimmerer’s latest, The Serviceberry, is a well-spent afternoon.

Bibliography:

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Scribner, 2024.

A Few Great Quotes:

“To name the world as gift is to feel your membership in the web of reciprocity. It makes you happy-and it makes you accountable. Conceiving of something as a gift changes your relationship to it in a profound way, even though the physical makeup of the ‘thing’ has not changed” 22).

“How we think ripples out to how we behave. If we view these berries or that spring as an object, as property, it can be exploited as a commodity in a market economy. When something moves from the status of gift to the status of commodity, we can become detached from mutual responsibility. We know the consequences of that detachment” (25).

“In a gift economy, wealth is understood as having enough to share, and the practice for dealing with abundance is to give it away. In fact, status is determined not by how much one accumulates, but by how much one gives away. The currency in a gift economy is relationship, which is expressed as gratitude, as interdependence and the ongoing cycles of reciprocity. A gift economy nurtures the community bonds that enhance mutual well-being; the economic unit is ‘we’ rather than ‘I,’ as all flourishing is mutual” (32-33).

“The challenge is to cultivate our inherent capacity for gift economies without the catalyst of catastrophe. We have to believe in our neighbors, that our shared interests supersede the impulses of selfishness. There is a tragedy in believing the proffered narrative of our system, which turns us against each other in a zero-sum game” (44).

“Libraries are models of gift economies, providing free access not only to books but also music, tools, seeds, and more. We don't each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free book” (56).

“Libraries, parks, trails, and cultural landscapes we regard as public goods; they are what we call ‘common resources’—meant to be shared and cared for by the people who use them. They become possible when we pool our excess dollars in the form of taxes for the common good” (56-57).

“What would it be like to consume with the full awareness that we are the recipients of earthly gifts, which we have not earned? To consume with humility? We are called to harvest honorably, with restraint, respect, reverence, and reciprocity” (63).

“Gift economies arise from an understanding of earthly abundance and the gratitude it generates. A perception of abundance, based on the notion that there is enough if we share it, underlies economies of mutual support” (75).

“[T]hat they function well in small, tightly knit communities. You might rightly observe that we no longer live in small, close-knit societies, where generosity and mutual esteem structure our relations. But we could. It is within our power to create such webs of interdependence, quite outside the market economy” (91).